A Love Letter to a Giant

a conventional Google

I am a Googler who wrote this on my own time about my own opinions.

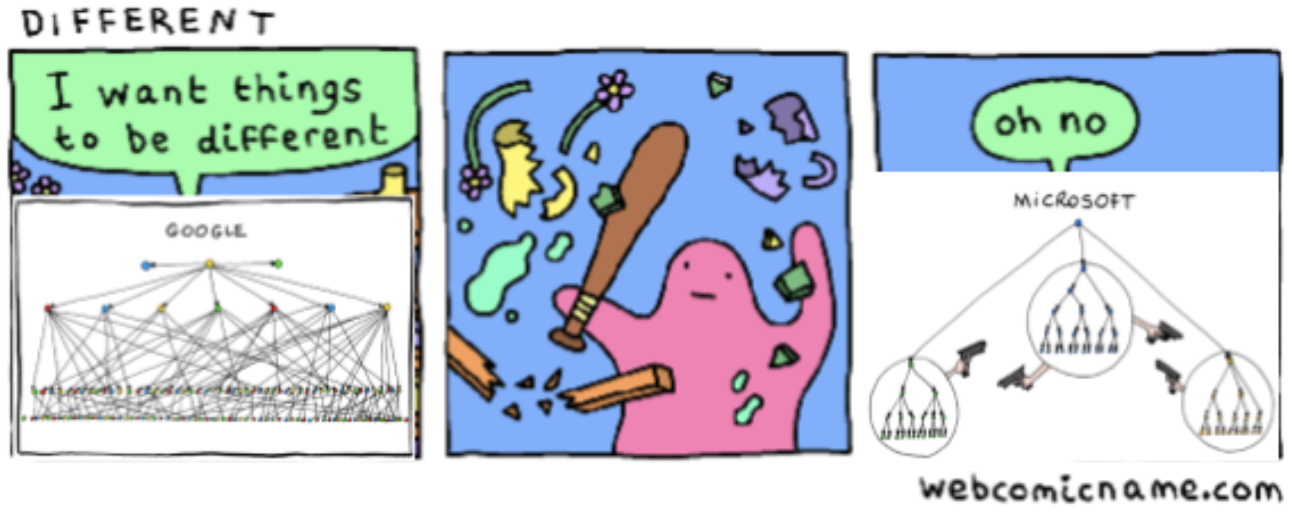

Google wasn't designed to be a conventional company. This is what Google founders Larry and Sergey repeatedly declared in their IPO letter, "An Owner's Manual for Google's Shareholder". Google in its early years revolutionized the world repeatedly with technologies like Gmail, Maps, Drive, YouTube, Android, and Chrome. Unlike most firms that stick to their "primary expertise" or adopt new technologies, Google consistently innovated and revolutionized the world. Instead of following the market, Google consistently led the market and raised the bar for all technology companies.

There are innumerable number of differences between present day Google and Google back then. I believe the simplest but most profound difference is the ability for ideas to flow freely and for people to freely associate. New ideas inject uncertainty. New ideas could completely overturn existing organizational structures and processes. And the young Google embraced that uncertainty as that allowed them to continuously innovate. In a conventional company, the overturning of existing organizational structures are strongly resisted for fear of the unknown and one's place in a new world order introduced by new ideas.

I have been at Google now for seven years. I have witnessed a constant struggle with Google's identity, what it means to be googley, and whether or not it has finally become a conventional company. 2024 may contain the clearest evidence of Google becoming a truly conventional company. The Google of the 2000s wouldn't have engaged in illegal anti-competitive behavior. Nor would it have invented AI technology in 2017, failed to bring it to market, and only play catchup when a different technology company, OpenAI, brings the seven-year-old technology to market.

Googleyness, a core idea of Google culture, embodies its unconventional roots. Googleyness is difficult to describe, and everyone has different ideas on what googleyness is, exactly. To contrast googleyness, I describe a conventional culture in the modern era to be consisting of de facto patronages that incentivizes people to fight for by hoarding information to shape narratives.

The primary goal of this letter will be to try to describe what a conventional company might look like compared to an alternative like a "Googley" one. I will share with you my direct observations and what I extrapolate them to mean for the culture as a whole. Perhaps we can take another step closer to understanding how a company has regressed from a company that was always raising the bar to a company that has become so incapable of delivering its own inventions unless another company does it.

A Tale of Two Googles

Allow me to start with an anecdote with my direct observations containing most of the most salient properties of Googleyness. It started with a draft of a roadmap. The authors, reviews, and approvers of this roadmap included illustrious Google fellows and directors managing thousands of engineers. I disagreed with one of the draft decisions, and I left a comment to that effect. This evoked a response, and a written debate ensued to refine our respective points and stances. This was followed up by multiple meetings with very senior engineers (seniority levels at Google go up to L10, and these meetings included L6, L8, and L9). At this point, I understood more of the complexities behind our disagreement, and I never realized that this disagreement would call the attention of such senior levels. I have written many opinions during my time at Google, and many were ignored. Even so, I restated the gist of my original point and made some clarifications in response to questions and comments in these meetings.

Other than my initial comment on the roadmap, I did not initiate anything else. I responded to comments, and I attended these meetings to which I was invited. I was pleased to simply get my opinion on the record. Actually, I was more than pleased at the opportunity to refine my ideas through vigorous debate, and to better understand the original position that I disagreed with. And after all that debate, I could see the argument going in either direction, although I personally preferred my own argument of course. I was surprised a couple of months later that they had reversed their original stance in the final, published roadmap and adopted the stance I advocated.

A Different Story

Now let me tell you a different story. In a different part of the Google organization, I had been feeling very frustrated with what I viewed as many very costly missed opportunities that the organization could benefit from learning. I figured that my own definition of success may have been different from the organizational definition of success, but I was getting very different definitions of success depending on who I asked. I stumbled upon the fact that my manager five levels up (that is, my manager's manager's manager's manager's manager's manager) hosted office hours. I signed up for the next availability for the next month - VPs are busy! Someone in my management chain noticed it on my Google calendar and scolded me for hours. It escalated and some in my management chain voiced support for my choice to attend anyone's office hours, even a VP. It's office hours, after all. That did not stop the haranguing though. Different people, including managers, voiced their private support, but that did not stop others from forming groups and spending hours to pressure me to stop. I attended one more office hour of the manager five levels up. I mentioned that there may be people in my management chain who report to them telling me not to attend their office hours. They brushed off my concern. They no longer have office hours available.

Extrapolations

These are just two of the most "extreme" anecdotes I have consisting entirely of my own direct observations. In a "Googley" culture, I felt like I could behave in ways that I felt completely natural without any fear of consequences. I could talk to anyone who agreed to talk to me; I could write whatever opinion I wanted about our technology or roadmaps and the worst thing that would happen is that I would be completely ignored; I could ask people and teams for their roadmaps and definitions of success and I would get it. In fact, roadmaps and metrics for success were normally very accessible, and me asking for them often got teams to make it even more visible since apparently I had to ask them instead of finding it naturally.

I often attributed this culture of googleyness to the academic roots of Google. The founders were PhD candidates in Stanford when they developed the Google search engine, and they initially wrote a peer-reviewed paper on the search technology that propelled Google into overwhelming success. The googley culture of transparency and review has many parallels to the expectations of transparency and review of scientific publications.

In the "conventional" culture, I've had multiple people complain to different managers of mine about public statements and comments I have made. These interactions struck me as extremely political in nature since they could communicate any issues with my public comments with their own public comments. In the pursuit of transparency and opportunities to collaborate, I would ask different teams for their roadmaps and success metrics that they were currently measuring, and I would get stonewalled. I would slowly expand the recipients of my inquiry, and one of the original recipients would finally respond. I would often get evasive non-answers, such as "thank you for the feedback".

Heck, over the years, I didn't even understand many of my own teams' roadmaps and success criteria. During various all-hand meetings, leaders often responded with some form of "we're working on it" and "we're looking forward to sharing them with you when they're ready". Whenever it came to reviewing success though, these reviews always asserted that we've hit 100% of our goals.

Reactions

When talking to my coworkers within the "conventional" culture, I always felt like the weird one. People often agreed, with varying degrees of agreement, that I should be able to ask the questions that I ask and make the comments that I make. Even if it was considered allowed, everyone would insist that they would not dare. People would have different levels of recognition of the suppression of dissent. Some found the behavior and attitudes in response to my public questions to be appalling and upsetting. Some found such behavior appalling but accepted it as simply as a matter of fact of how the world simply worked. On the other hand, some found my behavior to be appalling by being disrespectful and unnecessarily antagonistic.

When talking to my coworkers within the "googley" culture, their responses often had a predictable level of concern and skepticism. I appreciated the skepticism when I was challenged with questions about what I observed and what I was extrapolating from those observations. I would often have to recount many different anecdotes to demonstrate multiple pieces of evidence to successfully argue that these patterns of behavior were not one-off occurrences.

De facto patronage

Google may be an unconventional company, but it exists within a conventional world. In a conventional world, one does not intrinsically gain power by inventing something. Wozniak may have developed the Apple I, but Steve Jobs was in charge of the company. A natural way of gaining power is to have people put you in power, and a natural way to convince people to do that is to give those people what they want in exchange for power. For example, Wozniak developed the Apple I and then sold his stake in Apple for $800; he didn't fight for but instead gave it all up.

Accountability is both a threat and an asset to established political power. Accountability is a double-edged sword that can diminish someone's power, but trying to hold the powerful accountable can mean that a target is placed on your back, even if you're not interested in power. Think of how some powerful people respond to some journalists who criticize them. This also means that powerful people would be hesitant to hold other people accountable. They may view it as an unnecessary risk to their own power. Thus, as authorities consolidate, authorities may hoard information to shape narratives, and each authority takes care to shape narratives that maximize their own benefit and avoid needlessly detracting from anyone else's narrative. People organize into groups/teams/tribes that are mutually beneficial de facto patronages where these groups comprise of constituents who support patrons who champion a narrative that benefits the group/team/tribe. This can mean that the best decisions for Google as a whole may be different from a narrative that a patronage can push. The best decisions for Google to make require information that is aligned with reality. However, when there are strong disincentives to dispute a narrative, and dissent is suppressed, the narratives pushed by patronages can depart from reality very rapidly. This results in an environment where Google cannot make optimal decisions because much of the information is not grounded in reality.

In a world where information is power, hoarding information is hoarding power.

Inventions present a risk of creative destruction, and thus inventions are also a threat to established political power. Inventions are intrinsically disruptive, and if there is a choice to suppress an invention, that would be the choice that most preserves the status quo. There are famous public examples, such as the time Kodak invented digital photography and never adopted it and the time Xerox demonstrated the computer graphical user interface and the mouse to Apple engineers while Xerox sat aside to watch Apple use that technology to become the biggest company in the world. Finally, there may be another example, when Google invented the transformer architecture in 2017 and did nothing with it until 7 years later where it is playing catch-up with OpenAI who used that technology to develop ChatGPT. To Google's credit, it won't sit aside like Xerox did, but instead it declared a code red to rapidly catch up with OpenAI.

Just these two principles of suppressing information and inventions may be powerful explanations for why companies can stagnate and degrade in their craftsmanship and innovativeness. Google was not designed to scale up by incrementally making minor improvements. The founders, Larry and Sergey, understood how this is how the conventional world works and was not a part of their original vision for Google. "As a private company, we have concentrated on the long term, and this has served us well... In our opinion, outside pressures too often tempt companies to sacrifice long term opportunities to meet quarterly market expectations". While Larry and Sergey were concerned about "outside pressures", perhaps they overlooked the forces that may develop internally that would also sacrifice long term opportunities to maintain the status quo and existing power dynamics internal to Google.

Critical juncture

Critical junctures are periods of time that give opportunity for great change. Acemoglu and Robinson, winners of the 2024 Nobel Prize in Economics, described critical junctures arise due to "a major event or confluence of factors disrupts the existing balance of political or economic power". I believe Google has arrived at such a juncture. Google stock performance stagnated 2022-2023. Google laid off 12,000 employees. Googlers unionized into the Alphabet Workers Union. Google has been ruled to illegally monopolize online search. Google reduced management roles by 10%. With investor excitement for AI and LLMs, stock performance has been good for 2024 and started an artificial intelligence arms race that Google should have had a seven year lead on.

Strong stock performance can reduce outside pressures on the company, and this may be an opportunity for the people at Google to seriously consider its current trajectory. Google now has a track record extending over decades that we can now examine. If we were to seriously compare Google's first decade with Google of the past decade, are we excited by its trajectory? How did Google fumble so hard on a technology it invented 7 years ago? Could there be other innovations that Google has invented but will simply not capitalize on unless forced to?

I admit that if we look at stock prices, GOOG still outperformed the S&P 500 in the past decade. We have to ask where that growth is coming from. Is that growth from innovation? Or from anti-competitive behavior and enshittification? Is the Google of the past decade simply resting on the laurels of the Google of its first decade? We must truly ask ourselves - are we becoming a conventional company? Do we want to be?

Recommendations

Up to this point, I have laid the foundation for why and how Google is becoming a conventional company. If this foundation is at all solid to you, then here are some recommendations for how Google can become a little more unconventional again.

These recommendations are also inspired by the work from Robinson and Acemoglu and their work in describing how institutions that distribute political power in a pluralistic manner and institutions that centralize authority are institutions that promote prosperity.

Bring back what worked

Bring back the original Googlegeist. Information is power, and the original Googlegeist allowed Google to produce performance metrics on different leaders, increasing accountability.

Bring back live questions to top leadership. These used to occur on a weekly basis at Google's relatively famous weekly TGIF/TGIT events. These live questions facilitated the free flow of information where concerns can reach top leadership, drive the conversation across the company, and set the tone on how the company as a whole addresses concerns. Larry and Sergey may have been able to push an unconventional culture of academic transparency by regularly communicating in such candid settings.

Stop policing internal message boards. Either make certain forms of speech against official Google policy or simply allow them. This inconsistent control of speech are power plays that reduce the free flow of information at Google. The inconsistent controls on speech are also signs of different powers forming dominions over domains where they can assert influence. Google already has some common sense controls for certain forms of speech when it relates to security, privacy, or confidentiality. It should make a consistent policy in that regard.

Free flow of information

As previously stated, information is power. This is already especially true in the modern economy; it is even more so in a giant technology company! This recommendation is to make it official Google policy to have speech that would be actively protected from suppression. Speech should be protected in a way such that suppression of speech would require specific reasons, such as privacy, security, confidentiality reasons or some reason associated with the Google Code of Conduct. This could be instituted as a clarification of the Google Code of Conduct and its "Harassment, Discrimination, and Bullying" and "Safe and Healthy Workplace" sections in particular. This would not be an outrageous clarification.

For example, in the Google Code of Conduct training, it would be appropriate to report a coworker whose gaze may have lingered inappropriately long on a coworker's chest. This report may result in an HR investigation that concludes that the viewer was simply spending time reading the text on a coworker's shirt. Likewise, this clarification in Google's Code of Conduct could have the Code of Conduct training updated such that managers privately criticizing public speech could be reported to be investigated.

Basic information requirements

Require teams to have common-sense information available about the team: regularly updated roadmap and success metrics. These should be treated as nothing more than statements of intention rather than a contract. For example, a team may have a quarterly roadmap to initially improve LLM accuracy, but such a team may reasonably pivot to improve LLM efficiency in the middle of the quarter.

Teams should also have an official, desired headcount. Another frustrating aspect of my work experience has been surprise failures to backfill positions and surprise team transfers. This hidden information about team sizes only allows secret exchanges of political favors. As teams shrink, managers can claim that they are "achieving results with less resources". As teams grow, managers can claim that they are now responsible for a larger empire. The scope of the work grows and shrinks with headcount changes, and if the scope of the work can shrink from natural attrition, then perhaps the work was never a priority to begin with. If the scope of the work can grow from team growth, that seems opportunistic rather than intentional.

Management chains

Google has already reduced management roles by 10%. There isn't an explicit recommendation here, but I anticipate that, if enacted, these recommendations will cause more pressure to further reduce management roles. Management chains can get quite deep at Google, but theoretically, with ~170k employees, if managers have 8 reports each, management chains should be at most 6 layers. With transparent communication, there would be less need for middle managers to control the flow of information that stabilizes existing organizational structures.

Rationale

Google wasn't designed to be a conventional company. The recommendations here are only codifications of Google's unconventionality that wasn't previously codified. There are hints of these unconventional practices in Google's famous site reliability engineering practices. Google has written about its post mortem culture that requires the free flow of information and the protection of speech with its culture of blamelessness in its book "Site Reliability Engineering: How Google Runs Production Systems" (2016). Its postmortem culture utilizes an "open commenting/annotation system" that makes "crowdsourcing solutions easy and improves coverage". Engineers are ultimately responsible for the flow of information that keeps it blameless: "blameless postmortems are ideally the product of engineer self-motivation".

The recommendations are also based on recommendations by Acemoglu and Robinson's work on "Why Nations Fail" (2012). Google is so large and complex that the factors of prosperity in a nation-state should apply to Google as well. A couple of practices that improved the prosperity of a nation was the centralization of authority and the pluralistic distribution of political power. In the recommendations in this letter, the pluralistic distribution of political power comes in the form of the freedom of speech; information is power after all. Just like journalists keep power in check, so can engineers in an engineering company. This reduces the concentration of power into those who have climbed the corporate ladder and forces disagreements and dissent to be debated rather than suppressed.

The authority to regulate speech should be centralized by the Code of Conduct, and consequently the authority to protect speech is conferred by the Code of Conduct to authorities that enforce the Code of Conduct.

A choice

Google demonstrated what an unconventional company is capable of a couple of decades ago. An unconventional company doesn't guarantee success, but neither does a conventional company. The situation is complex and requires considering a multitude of perspectives, so allow me to ask these questions for the reader to consider the possible answer from the different possible perspectives.

-

How do we think a company like Google managed to invent LLMs in 2017 but failed to bring it to market until a competitor forced it to 7 years later?

- I honestly don't know the answer to this question, even an internal answer to this question, so I will presume there is no official answer that is widely promulgated internally.

-

Do shareholders want these decisions more transparently driven, at least within Google and among Googlers? Perhaps take more advantage of the massive intellectual capacity and engineering resources at Google to assess and manage risk? Or is the preference a more conventional flow of information that is controlled by people who succeed at climbing the corporate ladder?

- Consider Boeing where perhaps its stock price performed predictably well for a period of time, but there are high-profile failures of Boeing airplanes and reports of suppression of engineering concerns.

- I would also find it hard to believe that the inventors of the technology would fail to understand the potential of their own technology. Disempowering inventors is consistent with, for example, the inventor of an AI library (Keras) explaining that integration choices of their own technology being out of their hands and dictated by high level leadership at Google.

- How much more returns could Google have realized if Google had seriously started developing the LLM market 7 years ago when it revealed the technology to the world?

-

What other technologies might there be that companies like Google are capable of inventing but fail to bring to market?

- Consider Kodak and Xerox. Again, these are just examples that are publicly known and notable.

- Are there forces like a fear of creative destruction that keep technologies, those small and those world-changing, from being developed?

Google should be grateful to OpenAI for launching the generative AI revolution. It failed to do so itself for at least 7 years until OpenAI finally launched ChatGPT. If Google really is becoming a conventional company, if Google really is unable to bring world-changing technologies to market (even those invented by Google); then I would expect other aspects of Google to become more conventional as well. It would be hard to justify such an unconventional pay structure or such an unconventional array of amenities either. When we look at conventional pay structures, VPs make 208k-379k. When we look at Google's unconventional pay structure, that would represent the lower end of the engineering pay distribution. It is unconventional to expect every engineer to have an impact that the typical VP has, and engineers need to be sufficiently empowered to achieve such impact. Perhaps it should come to no surprise that Sundar Pichai, Google CEO, said "There are real concerns that our productivity as a whole is not where it needs to be for the head count we have." And 2023-2024 have shown that Google will do massive and continual layoffs if its stock does not experience a certain level of growth, regardless of the cash it has. Now that the AI excitement has allowed the stock price to grow, we can take a moment to seriously consider our long term trajectory and if we have the right institutions that allow Google to innovate with all of its massive engineering resources like it did in its first decade when it was even smaller!

The Google SRE book attributed Google's blameless culture to have originated in "the healthcare and avionics industries where mistakes can be fatal". And there is evidence that this culture of blamelessness and transparency existed in these industries. According to John Oliver on Last Week Tonight:

... one [Boeing] project leader in the '80s and early '90s is remembered for saying “no secrets,” and “the only thing that will make me rip off your head and shit down your neck is withholding information.” ... But it's pretty clear that we're a long way from that culture today.

There have been numerous official reports of suppression of concerns from engineers at Boeing as well as two sudden mysterious deaths of Boeing engineers who were blowing the whistle on Boeing. Healthcare has been in such shambles that most Americans blame the healthcare system for the cold-blooded murder of one its CEOs. Despite such public animosity, the people around the murdered CEO, Brian Thompson, described him in heartwarming terms: devoted father, hard worker, reliable friend, ally to special Olympics and Olympians. And I'm inclined to believe these generous testimonies about Thompson. A blameless culture recognizes the broken system rather than individual fault. I may have brought up Thompson, but I don't really blame any CEO. I have enjoyed working with all my coworkers despite a broken system. I don't hate the player; I hate the game. And although the modern economy and politics have made great strides in distributing political power in a pluralistic manner, we clearly live in a broken system. It is my hope that this letter describes some of the rules to the conventional game that we don't even realize that we are playing, and perhaps we can fix the game by playing by the unconventional rules Google played in its early years! Perhaps we can look at avionics and healthcare to see where Google's trajectory may be leading to, and we should ask ourselves if that is what we want to become.